Well this week has included some great physics colloquia discussions on dark matter and astrophysical constraints on the currently unknown dark matter particle characteristics. Also, I received a little six-inch machined bar, costing about $10/inch (I don't know why these little telescope accessories costs so much) so that I can more easily mount my camera/telephoto lens combination and the red dot finder all at the same time on my lightweight, non-tracking tripod. As you recall, this setup can be easily moved and installed with just one hand and I can make some "science" type measurements very easily without a lot of setup time. This time I am investigating whether I can see M1, The Crab Nebula, in city lights. But first,

let me show you the new setup.

See now how the camera is mounted on the left hand side of the new mounting bar and the red dot finder is mounted on the right hand side. The really new feature is that now there are separate knobs, with 1/2-20 threads, that can be used to individually adjust and tighten either the camera or the red do finder, thus making alignment much easier. Now, I can move position the camera so that some distant object is centered in the Live View screen and then adjust the red dot finder so that the red dot lies right on top of the selected object. This is now so much easier that what I had before when both camera and red dot finder were attached to the tripod using just one, single 1/4 - 20 screw.

|

| Now using six inch adapter bar to mount camera and red dot finder on tripod (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

Ok, that is the new easy to use setup, now the target this time is the Crab Nebula (M1). Nothing special about selecting M1 as the target other than I don't think I have ever actually tried to look at it. Last week Retired Semiconductor Physicist and OCA member, John, asked if I had seen the Crab Nebula, and darn, I couldn't really remember ever looking at it. Winter is a good time to see it, but we have been clouded out the last two months at Black Star Canyon, so, I thought I might as well just try and make an attempt at seeing it even in city lights.

Just for convenience, see the beautiful image (courtesy of NASA) below. Now, I certainly don't expect to see anything like the quality of this image, nor of the quality of image that many of our OCA astroimagers get either, mainly after stacking many long exposure images. Anyway, we can dream about seeing something with our own eyeballs anyway.

|

| Crab Nebula (M1) Courtesy of www.nasa.gov |

The approach used here is to make an actual measurement of the night sky brightness with an IPhone app, Dark Sky Meter, which was first brought to my attention by Moved to Dark Mountainous Skies, David. Thanks for the tip, David! The screenshot image, below, shows the measured dark sky, taken by just stepping outside the observatory. The sky was cloudy, the street lamps and house lights were all on, and the moon was almost full, all of which contribute to bright city lights view.

|

| Using IPhone Dark Sky Meter app to estimate sky darkness (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

Oh, oh, this M1 surface brightness is much dimmer than the measured night sky brightness, so based on this estimate it is not likely that we will be able to see M1 in these bright city light views. But, I wonder if this estimate is strictly correct or not? The near full moon and street lights certainly contribute to making the measured value as bright as it is and it is certainly not conducive to getting your eyeballs accommodated to the dark skies. But, I am not interested in getting my eyeballs accommodated this time because I am taking a photograph and don't really care what my eyeballs say, other than that I can find the reference stars such that I can point the camera in the right direction. Also, I can see the overhead clouds, so this leads to believe that they are visible due to the reflected light from the city lights, etc., on the ground and reflected light from the moon.

But my camera is pointing at a relatively dark spot on the sky and should not receive much light from the clouds, etc. Also, the Dark Sky Monitor is measuring the light from all of these objects, the bright moon and ground lights reflected back down by the overhead clouds, so, if I am correct in reasoning so far, my camera and telephoto lens will not see a big part of the night sky light that will obviously affect my eyeballs and dark sky monitor. So, maybe, just maybe, we still might be able to get a bit of a glimpse of M1.

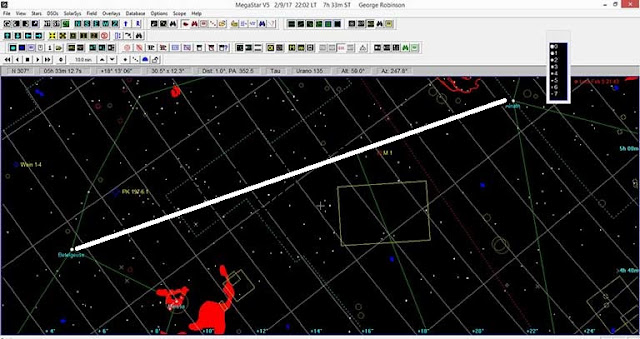

So, outside I go and try to find M1. Now, I can't see M1 because it is too dim, but I found that M1 lies almost directly on a line going from Betelgeuse, magnitude 0.4, in Orion and one other dimmer star, Elnath, magnitude 1.6. See the chart view below. The camera field of view for 300mm focal length is 2.9 degrees by 4.4 degrees.

Now, I could just barely, and on just an occasion here and there, see Elath, because of clouds, but I tried to guess where M1 was based on going down the line from Betelgeuse, which I could always see. But, as luck would have it, my guess and aim was off a bit. The camera field of view is shown as a white rectangle in the screenshot and M1 is located just below the thick white line. Alas, the location where the camera is pointing, as identified with the image analysis of Astrometry.net, shows that my pointing was not good enough to include the location of M1 in the field of view. I was off by just one camera frame of view.

|

| Megastar plot showing M1 just out of camera field of view as white rectangle and desired star hopping path along white line |

Darn! That is just what happens in the world of astronomy. The clouds were coming in even heavier, which started out at about 65% overcast, and now it was getting hard to even see any bright stars, so I just brought everything back inside.

So, the answer to the question of being able to see M1 in city lights views remains unanswered by this investigation. Normally, for dim objects, one can just increase the exposure time, but this can't be done here for two reasons. First any exposure time greater than about 2 seconds with my non-tracking mount will have streaking and trailing in the image and I would have to use the tracking mount to go to longer exposures. Secondly, and most importantly, if the target is dimmer than the background night sky, there is not much chance of seeing anything in that the object will be completely washed out.

Oh, well, that is about enough on this topic, even though I will try this experiment again later after the current rain clouds go away. If you want to read up more on surface brightness and such topics, check out the Cloudy Nights web page by clicking on the web reference on the blog main page. Reading some of the comments there leads me to believe that many of these estimates of darkness and naked eye observing limits should be taken with a grain of salt. Check it out. In fact, I intend to finish off the afternoon with a whole lot of grains of salt on my margarita(s).

Until next time,

Resident Astronomer George

There are over 200 postings of similar topics on this blog

If you are interested in things astronomical or in astrophysics and cosmology

Check out this blog at www.palmiaobservatory.com

No comments:

Post a Comment