This week I had every intention to try to find and photograph the nearby comet 41P. I planned to use the observatory back patio because from there Polaris is visible to the naked eye and comet 41P, which with declination of +64 degrees, is located in the northerly skies, circling the north pole, with visible magnitude 6.6, too dim to see without a scope. So, the 80mm refractor was setup outside and as luck would have it, too many interfering factors made it impossible to get

an image, little alone even find the comet.

First of all, when I first set up to start observing, 41P was still about 40 degrees in elevation, but unfortunately the location was blocked by background trees. The patio location offered good viewing the rest of the evening, but this amateur ran into many other problems. Then I was using a new red dot finder as part of my alignment process and it projected a big very bright circle of red light that prevented me from seeing the dim star that was being used for alignment. I didn't find out, until the night observing was over, how to change the display setting to just be a red dot. I also found that as I tried to see the red dot, especially when the target star was high in the sky that my glasses would sort of fall down on my nose and I was trying to see the red dot just through above the top edge of my glasses and the red dot was just a out of focus blur. No wonder I often had trouble getting good alignments in the past> Anyway, I was eventually able to align on and find just one visible star, but this one star alignment resulted in the predicted location of 41P being off course by a degree or so. I just gave up and resolved to postpone the search for 41P until the next clear night when a different observing location would make multi-star alignment possible.

Just because that observing session ended in failure, we should not forget that even though astronomers mostly end up observing at night, we should not forget about daytime observing of the sun. It just happened that I checked the SOHO app for the latest solar activity and found that there are some giant sunspots visible right now. Check out the SOHO screenshot below.

|

| SOHO Satellite Solar Observation for April 1, 2017 |

Well, again, as luck has it for the amateur, the sun was already going down below the trees and I was able to just get this one shot. Note that there are no sunspots visible here. What happened? Ok, ok, I should have gone outside earlier in the day, but it seems that enough of the sun is visible that there should be some of the sunspots visible.

|

| Once you have a prediction go out and make the solar observation before it's too late (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

Since the forecast for nighttime observing was still filled with clouds, I just left the camera and telephoto connected and waited for the next day. Now, going outside earlier in the day, with the sun still high in the sky, it was time for the second attempt to get an image of the sunspots.

Ok, the image below shows the sunspots. Hooray, but why is their location so different from that shown in the SOHO image? No wonder the sunspots could not be seen in the first photo taken yesterday.

|

| Sun spot activity (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

Which way are the sunspots rotating on the surface of the sun? It is hard to tell from just this one observation, but take a look at the SOHO image for just two days after the one used two days before. Notice that the string of sunspots appears to have just moved across the surface of the sun. My understanding, after having a tour of the solar observatory on Lake Big Bear, is that most observatories such as SOHO and its images are plotted with the solar spin axis in the vertical position. But, my solar image was taken with just the camera oriented in true level, with respect to the ground, position, so the image is not aligned in any defined position with respect to the sun's rotational axis, so the two images do not line up on top of each other.

|

| SOHO Solar Activity on April 3 (Source: Courtesy NASA SOHO) |

Finally, we should report on the spectrometer project status and some of the homework performed to determine how to identify the Neon spectral lines needed to get a good calibration. Getting a good calibration is the starting point for doing spectroscopy, yet the observatory's spectrometer might not have the resolution capability to determine rotational velocities of the sun, for example, but is still key for doing spectral studies of stars and galaxies.

We consulted with Big Oil Retired Chemist, Dr. Arnold, who reported that we should be able to find plenty of spectral tables on the internet for Neon and other elements. So, after just a short search, we found the following:

|

| Neon spectrum (Source: Courtesy of www.trschools.com ) |

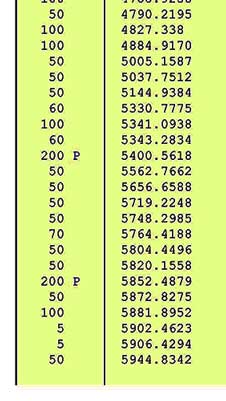

More specifically and importantly, a whole table of Neon spectral lines was found. Of particular interest is the table shown below that lists the relative intensity of various spectral lines, especially the line at 5944 Angstroms, which is used in the LISA operators manual as the calibration key.

|

| Spectral lines for Neon and relative intensities (Source: Courtesy of NIST ) |

This table helps define how to find the calibration line at 5944 Angstroms by comparing the relative brightness of surround lines. The question that Dr. Arnold asked is "Why didn't the spectrometer operators manual pick one of the brighter lines for calibration rather than just an ordinary line? Hey, yes, I wonder why that is the case? Anybody else have a good reason for that ? Anyway, thank you Arnold!

So that is about it for this time. Next post will include some reviews of events at two local meetings, including one on impact of global warming on ecosystems and one other on a live lecture by author Dava Sobel, offering her view on important discoveries in astronomy where the participation of women were of significant importance.

Until next time,

There are over 300 postings of similar topics on this blog

If you are interested in things astronomical or in astrophysics and cosmology

Check out this blog at www.palmiaobservatory.com

No comments:

Post a Comment