Well here we are in another busy week. We have upcoming conferences and also a chance to do some astrometry, which is now helping to maybe resolve the tension between two estimates of the Hubble Constant, in our search for finally trying ourselves to (though not yet) get an image of Pluto.

First up though we should mention two upcoming conferences. This week I am packing my bags to go to the AAVSO annual meeting in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where we attendees will also be able to tour two nearby observatories, including the Apache Point Observatory, where the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) was conducted. Should be fun and I will report from there, so stay tuned. If your are interested more in the activities of the AAVSO, check it out at: https://www.aavso.org/

For those of you staying here locally, especially all of you Martians, you have a chance to attend the Mars Society annual meeting held at USC on October 17-20, 2019. If you haven't already signed up, check out the details at: http://www.marssociety.org/conventions/2019/?mc_cid=314bf13140&mc_eid=794b11a172

But for now, lets get back to some of the latest news and astrometry is the key topic. First of all we have to report on some interesting papers about how the "tension" between estimates of the Hubble Constant might be resolved. After this discussion, we will describe our own efforts of using astrometry to determine if our search for own personal image of Pluto might be achieved.

First up, we need to remind ourselves of the ongoing tension in two different estimates of the Hubble Constant. This tension between two different, but well established, methods of estimating Hubble Constant has been around for several years now. The first method, based on using supernovas (see Nobel prize winner Riess and Schmidt teams) as standard candles has put the value of Hubble constant at 74.03 km/sec/Mpc, +/- 1.42 km/sec/Mpc. This value is compared to the Planck Collaboration's CMB measurement at 67.4 km/sec/Mpc, +/- 0.5 km/sec/Mpc.

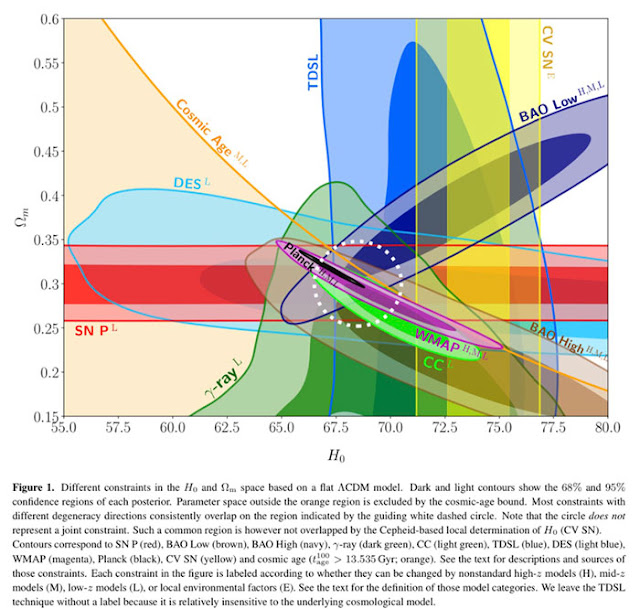

The whole panoramic view of measurements of the Hubble constant is shown in this drawing from one of Katie Mack (@Astrokatie). There are many studies and observations, not just based on astrometry and parallax that converge towards one point in the Hubble constant and total mass space. Her Twitter feed identified this graphic from one of her papers. The paper discusses some aspects of all of these separate lines of investigation.

|

| A tweet from Katie Mack (@AstroKatie) got the ball rolling (Source: K. Mack, et al, arXiv:1910.02978v1) |

Shortly after this paper came out, she referred us to another paper just released that identifies a plausible way of explaining and resolving the two different estimates. This referenced paper brings us right back to astrometry and how the latest Gaia data release is used to recalibrate and produce the most accurate yet rendition of Leavitt's law of connecting the period of the variable Cepheid stars and their absolute visual magnitude. Then knowing the apparent magnitude, you can work out the distance to the measured Cepheid, which can then be used to further calibrate other light sources and finalize the distance ladder used to estimate Hubble constant.

With this new calibration, the supernova derived distances and Hubble constant are then updated to a new value of 68.43 km/sec/Mpc, +/- 2.08 km/sec/Mpc, which now agrees quite well with the CMB derivation.

Wow, that is pretty neat and if the results of that paper and analysis are accepted and verified, the tension in the value of the constant will be resolved and unfortunately, does not require any new physics!

The chart below, from the paper by Louise Breuval, et al, shows some of the revised Cepheid data and the linear curve fit, which remains in the same form that Henrietta Leavitt first identified the relation. If you really like statistics, a lot of which I still don't get, and the other details be sure to check out the paper.

|

| Has Gaia data finally helped resolve the Hubble Constant tension? (Source: L. Breuval, et al, arXiv:1910.04694v1) |

Ok, back to observations that most astronomer wannabes can make in their own back yard. For several years now, I have tried to capture an image of Pluto, and have not been successful for a variety of reasons. These failed attempts were documented in blog postings of December 6, 2017 and December 17, 2017. You can check those out for the sad events there.

Now after attending the OCA general meeting, OCA Chris Butler, in his "what's up" presentation alerted us to the configuration of Pluto and Saturn. Well, I can see Saturn with my naked eyes and knowing now that Pluto is just a few degrees up and to the left of Saturn, means that I can easily point my non-tracking tripod and DSLR camera at that spot of the sky. Thanks for that alert, Chris!

So, when the sky was dark, well as dark as it gets in our city lights polluted view, it was easy to carry out the camera and tripod to do a couple of quick images of the night sky. The camera was pointed so that the Saturn was just visible in the lower right hand corner and with DSLR telephoto lens set to about 134-150mm, the location of Pluto was supposed to be about dead center. The first image with 8 second exposure is shown below.

|

| Looking for Pluto with Saturn in lower right of DSLR image, 135mm, 8 seconds (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

Now the first steps in trying to find Pluto in this image is to look up the right ascension and declination. This is easy to do with any convenient software, which in this case is just the Go Sky Watch app on the iPhone. Ok, so Pluto is at RA = 19h 29' and Dec = -22 degrees and 23 minutes.

|

| Using the Go Sky Watch app to find Pluto RA and Dec (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

Look at the results page from Astrometry.net below. We can see that even though the image includes star streaking, the image was after all taken with a non-tracking mount, the online software was able to identify the sky location. The center of the image frame was pointed at RA = 19h 27m and Dec = -22 degrees and 59 minutes. The image was wrongly labeled "Saturn_lowerleft" when Saturn was actually positioned to be in the lower right hand side. Anyway, Hey, hooray, the center is within about a half degree of Pluto's predicted location!

|

| Searching for Pluto using astrometry on 61 second DSLR image (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

So, where is Pluto supposed to be in this image? Well, let's use another iPhone (or equivalent) app, in this case Sky Safari Pro to show us where Pluto should be found in that image. You can see the Pluto is expected somewhere between the X3sgr and 50Sgr.

|

| Sky Safari Pro app screenshot shows location of Pluto (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

OK, So here is that cropped 60 second image and you can take a look and see if you see Pluto or not? Hmm, I don't see Pluto in this image! We really didn't expect to see Pluto in this case for several reasons:

- The city lights night sky is too bright to see Pluto

- The non-tracking mount and resulting star trails lowers SNR for any possible dim Pluto

- But maybe with a tracking mount and dark skies, like in Borrego Springs, it might be done

|

| Ok, Pluto could be in this 61 second DSLR image (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

So, the technique of finding where Pluto should be located, as pointed out to us by OCA Chris Butler, is doable and has been verified here. But the local sky is too bright. Previous estimates of the local night sky brightness at this observatory, as described in this blog for posts of December 6, 2017 and December 17, 2017, where the local sky brightness was measured to be about magnitude 14.3, which is as bright as Pluto, and magnitude = 18.5 at the nearby OCA Bow Swenson Star Party site. So, it might be possible to capture Pluto there or at the OCA Anza site. Previous other failed attempts of capturing an image (or really just a few pixels) of Pluto were described in earlier blog posting in Sept/Oct 2016. Check them out for the sad story and lessons learned.

The good news is that now we know how to find Pluto in the night sky, the upcoming dark sky Nightfall Party in Borrego Springs might be an ideal time to finally capture a little bit of Pluto!

Until next time,

Resident Astronomer George

Be sure to check out over 300 other blog posts on similar topics

If you are interested in things astronomical or in astrophysics and cosmology

Check out this blog at www.palmiaobservatory.com

No comments:

Post a Comment