Well this week the clouds opened up enough that we could see if there are a growing number of sunspots or not, and our short wait for the first "chirp" alert from our Gravitational Wave Event app finally ended with our first series of alerts for LIGO/VIRGO S190510g event. But first of all, Happy Mothers Day to everyone, especially the mothers, for whom we are always grateful!

Now, let's review some images of the sun that were possible when the clouds opened up enough to let the possible sunspots show up. When it was possible to see your own shadow, I went outside with a 600mm telephoto lens to check on the status of the sun. In this photo we see the DSLR with 600mm lens, filtered with a ND100000 solar filter, attached to the lightweight Sky-Watcher mount. Yes, my friends at Amazon, delivered a spare filter, to replace the one I stuck my thumb through last week, and now we are good to go! This time the replacement filter is thick glass and not the flimsy mylar film like on the previous, now broken, filter!

|

| Looking at the sun and spots with 600mm DSLR on Sky-Watcher mount (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

As you know, we have been evaluating the new lightweight Sky-Watcher mount, so it was great to have another opportunity to try out the mount, this time during the daylight. Initially, I couldn't find any way to just synchronize or align to the sun. I did get a message about not pointing a telescope at the sun, but could not find the sun or any other entry on the Sky-Watcher app screen to help me point towards the sun. Hmm, what to do? Well, we know that Mercury is pretty close to the sun at this time, so, I just slewed to Mercury and then tweeked the pointing to match up with sun. Finding the sun was made a little easier by using the attached red dot finder. No, not by looking for the red dot, but by just moving the camera pointing angle until the shadow of both cylinders of the red dot were aligned and fell right on top of each other. This condition meant that the camera was pointing right at the sun. (After the fact, I learned that the Sky-Watcher mount does have a solar tracking mode; it is located under the advanced settings page of the smartphone app).

The visible energy filtered image below shows two visible sunspots. Hey, maybe out quite sun is starting to wake up!

| |

|

|

| Expanded view of the two visible sunspots, 5/11/19 (Source: Palmia Observatory) |

So, enough on sunspots, readers of this blog will recall that in the April 28, 2019 blog posting, we had installed a Gravitational Wave Event app on our iPhone that would display an alert whenever the LIGO/VIRGO collaboration detected a possible gravitational wave event. Well, in the last several days the iPhone has been issuing a "chirp" alert, based on the chirp associated with the signal, detected by the LIGO collaboration, that is the result of gravitational wave emission from a compact object merger.

The following screenshot for the possible merger event, S190510g, was the first alert sent out to app users and other observatories around the world. This early alert shows the predicted probability that a binary neuron star merger is the source of the event at 97%, while the probability that it was caused by a terrestrial event is then the remaining 3%. The False Alarm Rate (FAR) was estimated at 1 event occurring in 37.59 years. Hmm, seems pretty solid so far that the event is a real merger!

|

| Screenshot for iPhone Gravitational Wave Event app announcing S1901510g event on 5/10/19 |

The detection of this possible gravitational wave event was broadcast to a wide variety of other observatories who could take advantage of the early warning and slew optical and other telescopes to the predicted location of the merger. The following screenshot shows the predicted possible locations of the merger. The top Mollweide project map was the initial estimated possible location and the bottom map shows the refined location released just 6 hours later.

|

| Screenshot from iPhone Gravitational Wave Event app showing possible sky locations for S190510g |

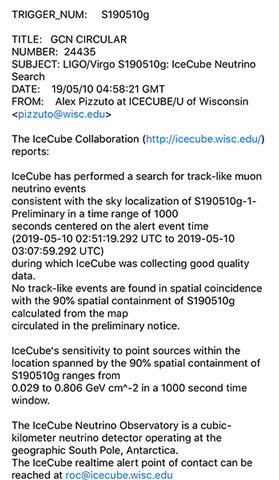

Not long after this initial "chirp" from the iPhone app, the phone just kept chirping regularly after that event as other observatories took up the challenge and pointed their telescopes at the predicted possible location to see if any electromagnetic counterpart could be detected. The first chirp report that I saw was from the ICECUBE collaboration from the South Pole. ICECUBE neutrino data did not indicate any signal from the possible locations. Not seeing any other detectable counterpart for the possible merger is not surprising at this early date because as we have seen from previously confirmed mergers, the optical and other counterpart signals often don't show up until many days later.

|

| ICECUBE was one of the first observatories to look for other counterparts for S190150g (Source: gracedb.ligo.org) |

So, after this chirp report, many other alerts showed up from many other observatories, that had interrupted their scheduled observing sessions, to check out the possible locations. No other electromagnetic counterparts have been discovered so far. Just in case you are considering going out and looking yourself for any optical counterpart, keep in mind that many of the observatories reporting no detected event, are reporting no detected event at the magnitude 20 seeing. So, you need a pretty good sized scope in a dark sky location just to enter the search for this possible merger.

Then this follow up circular releases the updated probability for the event being a merger of a binary star system at just 42%, with the probability of the signal being a terrestrial noise signal rising to 58%.

|

So, what is going to be he outcome of this mystery LIGO/VIRGO S190510g signal?

|

So, what is going to be he outcome of this mystery signal? We will just have to wait and see! We have not received any more chirp alerts to let us in on what is going on. There is no reported indication for the potential mass size of the merging neutron stars that could be correlated with the detected signal. All of this information and possible distance will not be released until much later. So, stay tuned or even better yet, sign up for the free app on your smart phone and wait for the next chirp alert! See, not even clouds can interfere with the GW signal, so you can always keep busy on cloud filled days and nights!

Until next time,

Resident Astronomer George

Be sure to check out over 300 other blog posts on similar topics

If you are interested in things astronomical or in astrophysics and cosmology

Check out this blog at www.palmiaobservatory.com

No comments:

Post a Comment